Is Infringement of a Foreign Patent akin to Highway Robbery?

Patents: Les Laboratoires Servier and another v Apotex Inc and others [2014] UKSC 55, [2014] 3 WLR 1257, [2014] WLR(D) 452, [2014] BUS LR 1217, UK Supreme Court

In Everet v. Williams (1893), 9 L.Q. Rev. 197, the highwayman John Everet sued his partner in crime Joseph Williams "for discovery, an account, and general relief" for dealing "with several gentlemen for divers watches, rings, swords, canes, hats, cloaks, horses, bridles, saddles, and other things" which they acquired "at a very cheap rate". The court dismissed the action on the ground that no action arises from a disgraceful act ("ex turpi causa non oritur actio"), fined the claimant's solicitors and ordered them to pay the defendant's costs. They got off lightly. Their client and the defendant were arrested, brought to trial for their "dealings" and hanged. You can find out more about the case in The Highwayman's Case.

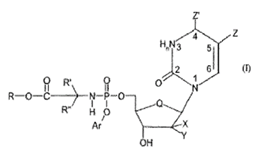

Fast forward to 2008. In Les Laboratoires Servier and another v Apotex Inc and others [2008] EWHC 2347 (Ch), [2009] FSR 3 (9 Oct 2008) Mr Justice Norris awarded the Apotex companies ("Apotex") £17.5 million upon the Servier group ("Servier")'s cross-undertaking in damages because the Apotex had been prevented from importing perindopril erbumine tablets from Canada and selling them in the United Kingdom by an interim injunction that was subsequently discharged (see my case note Interim Injunctions: Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Inc 10 Oct 2008). However, the manufacturer of those tablets in Canada by the defendants had become unlawful when Madam Justice Snider held in Les Laboratoires Servier and others v Apotext Inc, and another 67 CPR (4th) 241; [2008] FCJ No 1094 (QL); 332 FTR 193 that such manufacture infringed a patent for the drug that had been granted to one of the Servier companies. Servier had asked Mr Justice Norris for permission to amend their points of defence in the inquiry proceedings to plead Madam Justice Snider's decision but the judge refused to allow them to do so on the grounds that they had applied for permission too late. Servier appealed to the Court of Appeal which allowed the amendment (Les Laboratoires Servier and another v Apotex Inc and others [2010] EWCA Civ 279).

By the time the appeal was heard Apotex had already received the £17.5 million that had been awarded to them by Mr Justice Norris. The effect of the Court of Appeal's decision was that those moneys had to be treated as an interim payment. The question

The issue before their Lordships was whether the rule that had prevented one highway robber from claiming an account from another also prevented the defendants from claiming damages for being prevented from infringing a patent in Canada. The point was summed up neatly by Lord Sumption at paragraph [9] of his judgment:

The Court's first task was to determine what is meant by turpitude? At paragraph [25] of his judgment Lord Sumption said:

Lord Mance agreed with Lord Sumption that the appeal should fail on the simple basis that the manufacture and supply of product in breach of the Canadian patent would not have involved turpitude such as to engage the maxim ex turpi cause action non oritur.

Lord Toulson thought that Servier was attempting to extend the doctrine of illegality beyond any previously reported decision in circumstances where he could see no good public policy reason to do so.

The conclusion of the Supreme Court was that infringing a foreign patent is not like highway robbery. If anyone wants to discuss this fascinating case, public policy, interim injunctions or patent law in particular, he or she should not hesitate to call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or message me through my contact form.

By the time the appeal was heard Apotex had already received the £17.5 million that had been awarded to them by Mr Justice Norris. The effect of the Court of Appeal's decision was that those moneys had to be treated as an interim payment. The question

"whether a patentee who has obtained an interim injunction from this court to restrain infringement of a European patent (UK) which is subsequently held invalid should compensate the defendant for losses sustained as a result of being prevented by the injunction from selling goods manufactured by the defendant in infringement of a valid foreign patent owned by the same group of companies"came before Mr Justice Arnold in Les Laboratoires Servier and another v Apotex Inc and others [2011] RPC 20, [2011] EWHC 730 (Pat). His Lordship held that it should not and because such claim was barred by the ex turpi cause rule and he ordered Apotex to repay the £17.5 million that they had been awarded by Mr Justice Norris. Apotext appealed to the Court of Appeal which allowed the appeal (Les Laboratoires Servier and another v Apotex Inc and others [2012] EWCA Civ 593, [2012] WLR(D) 138, [2013] RPC 21, [2013] Bus LR 80. One of the reasons why the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal was that Apotex had agreed to give credit in the English litigation for any damages that might be awarded against them in Canada. Servier appealed to the Supreme Court.

The issue before their Lordships was whether the rule that had prevented one highway robber from claiming an account from another also prevented the defendants from claiming damages for being prevented from infringing a patent in Canada. The point was summed up neatly by Lord Sumption at paragraph [9] of his judgment:

"(1) Does the infringement of a foreign patent rights constitute a relevant illegality ("turpitude") for the purpose of the defence?Another way of putting it might be "is foreign patent infringement akin to highway robbery?"

(2) If so, is Apotex seeking to found its claim on it?

(3) Is Servier entitled to take the public policy point having given an undertaking in damages?"

The Court's first task was to determine what is meant by turpitude? At paragraph [25] of his judgment Lord Sumption said:

"The ex turpi causa principle is concerned with claims founded on acts which are contrary to the public law of the state and engage the public interest. The paradigm case is, as I have said, a criminal act. In addition, it is concerned with a limited category of acts which, while not necessarily criminal, can conveniently be described as "quasi-criminal" because they engage the public interest in the same way. Leaving aside the rather special case of contracts prohibited by law, which can give rise to no enforceable rights, this additional category of non-criminal acts giving rise to the defence includes cases of dishonesty or corruption, which have always been regarded as engaging the public interest even in the context of purely civil disputes; some anomalous categories of misconduct, such as prostitution, which without itself being criminal are contrary to public policy and involve criminal liability on the part of secondary parties; and the infringement of statutory rules enacted for the protection of the public interest and attracting civil sanctions of a penal character, such as the competition law considered by Flaux J in Safeway Stores Ltd v Twigger [2010] 3 All ER 577."There were some cases that suggested that the principle might be wider than that but apart from those decisions

"the researches of counsel have uncovered no cases in the long and much-litigated history of the illegality defence, in which it has been applied to acts which are neither criminal nor quasi-criminal but merely tortious or in breach of contract."His Lordship reasoned:

"In my opinion the question what constitutes "turpitude" for the purpose of the defence depends on the legal character of the acts relied on. It means criminal acts, and what I have called quasi-criminal acts. This is because only acts in these categories engage the public interest which is the foundation of the illegality defence. Torts (other than those of which dishonesty is an essential element), breaches of contract, statutory and other civil wrongs, offend against interests which are essentially private, not public. There is no reason in such a case for the law to withhold its ordinary remedies. The public interest is sufficiently served by the availability of a system of corrective justice to regulate their consequences as between the parties affected."He added, at paragraph [29] that there may be "exceptional cases where even criminal and quasi-criminal acts will not constitute turpitude for the purposes of the illegality defence." In his Lordship's opinion

"the illegality defence is not engaged by the consideration that Apotex's lost profits would have been made by selling product manufactured in Canada in breach of Servier's Canadian patent. A patent is of course a public grant of the state. But it does not follow that the public interest is engaged by a breach of the patentee's rights. The effect of the grant is simply to give rise to private rights of a character no different in principle from contractual rights or rights founded on breaches of statutory duty or other torts. The only relevant interest affected is that of the patentee, and that is sufficiently vindicated by the availability of damages for the infringements in Canada, which will be deducted from any recovery under Servier's undertaking in England. There is no public policy which could justify in addition the forfeiture of Apotex's rights."Having decided that point, the other two issues listed at paragraph [9] of Lord Sumption's judgment did not arise.

Lord Mance agreed with Lord Sumption that the appeal should fail on the simple basis that the manufacture and supply of product in breach of the Canadian patent would not have involved turpitude such as to engage the maxim ex turpi cause action non oritur.

Lord Toulson thought that Servier was attempting to extend the doctrine of illegality beyond any previously reported decision in circumstances where he could see no good public policy reason to do so.

The conclusion of the Supreme Court was that infringing a foreign patent is not like highway robbery. If anyone wants to discuss this fascinating case, public policy, interim injunctions or patent law in particular, he or she should not hesitate to call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or message me through my contact form.

Comments