Whisky Galore - Whyte and MacKay Ltd v Origin Wine UK Ltd

|

| Beinn Shiantaidh on the Isle of Jura

Photo Smith 609

Source Wikipedia

|

Jura is an island off the west coast of Scotland that is well known for its whisky. It is not to be confused with the Jura region of France which as it happens also produces whisky. According to the website Doubs Direct Whisky Jurassic consists of Scotch whisky that is matured in barrels that have contained the region's well known "Yelllow wine". It is worth noting that France is not just a great consumer of whisky. It has in recent years launched into whisky production (see Wikipedia Whisky en France). There is actually a website called France Whisky which keeps tabs on the French whisky industry.

However, none of that has anything to do with the case in hand which was an appeal to Mr Justice Arnold by Whyte and Mackay Ltd ("WM") against the decision of Mr George Salthouse in Jura Origin, Origin Wine UK Ltd and Another v Whyte and Mackay Ltd O-325-14 (23 July 2014) to block the registration of the sign JURA ORIGIN as a trade mark in respect of Scotch whisky and Scotch whisky based liqueurs produced in Scotland in class 33. WM had applied to register that mark on 6 Feb 2013. The application was opposed by Origin Wine UK Ltd ("Origin") and its associated company Dolce Co Invest Ltd ("Dolce") under s.5 (2) (b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994.

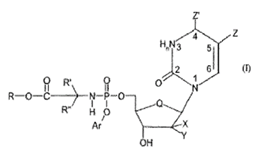

Origin relied on its UK trade marks ORIGINS for "alcoholic beverages (except beers); wine in class 33" and ORIGIN for "wines; alcoholic beverages" in class 33. Dolce relied on its CTM application for the registration of

in respect of "Alcoholic beverages (except beers), including wines" in class 33.

The hearing officer held at paragraph [26] that the goods for which the mark in suit was to be registered were identical to Dolce's CTM application but had only a low degree of similarity to wine in respect of which Origin's trade marks had been registered. At paras [35] and [36] he decided that the applicant's mark was at least moderately similar to the mark in suit. Finally, he decided that there was a likelihood of confusion including a likelihood of association of the WM's sign with the opponents' trade marks.

WM appealed to the court under s.76 (2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 on the following grounds:

"i) the hearing officer did not apply Medion v Thomson correctly;

ii) the hearing officer did not fully analyse the level of visual, aural and conceptual similarity between the respective pairs of marks;

iii) the hearing officer failed to consider whether the conceptual meaning of the word JURA in the Jura Mark outweighed the similarities between the respective marks due to the presence of the word ORIGIN;

iv) the hearing officer misapplied LA Sugar v By Back Beat; and

v) the hearing officer failed to take into account the principle that, where the only similarity between the respective marks consists of a common element which has low distinctiveness, that will not normally give rise to a likelihood of confusion."

The appeal came on before Mr Justice Arnold in Whyte and MacKay Ltd v Origin Wine UK Ltd and Another [2015] EWHC 1271 (Ch) (6 May 2015).

On the first point, the judge referred to his judgment in Aveda Corp v Dabur India Ltd [2013] EWHC 589 (Ch) and the Court of Justice of the European Union's decision in Case C-591/12 P Bimbo SA v OHIM ECLI:EU:T:2013:146, [2013] EUECJ T-277/12, EU:T:2013:146. At paragraph [18] of his judgment, Mr Justice Arnold said:

"The judgment in Bimbo confirms that the principle established in Medion v Thomson is not confined to the situation where the composite trade mark for which registration is sought contains an element which is identical to an earlier trade mark, but extends to the situation where the composite mark contains an element which is similar to the earlier mark. More importantly for present purposes, it also confirms three other points."

He set those out in the following paragraphs:

"[19] The first is that the assessment of likelihood of confusion must be made by considering and comparing the respective marks - visually, aurally and conceptually - as a whole. In Medion v Thomson and subsequent case law, the Court of Justice has recognised that there are situations in which the average consumer, while perceiving a composite mark as a whole, will also perceive that it consists of two (or more) signs one (or more) of which has a distinctive significance which is independent of the significance of the whole, and thus may be confused as a result of the identity or similarity of that sign to the earlier mark.

[20] The second point is that this principle can only apply in circumstances where the average consumer would perceive the relevant part of the composite mark to have distinctive significance independently of the whole. It does not apply where the average consumer would perceive the composite mark as a unit having a different meaning to the meanings of the separate components. That includes the situation where the meaning of one of the components is qualified by another component, as with a surname and a first name (e.g. BECKER and BARBARA BECKER).

[21] The third point is that, even where an element of the composite mark which is identical or similar to the earlier trade mark has an independent distinctive role, it does not automatically follow that there is a likelihood of confusion. It remains necessary for the competent authority to carry out a global assessment taking into account all relevant factors."

Applying that analysis to Mr Salthouse's decision the judge concluded at para [28] that there had been an error of principle in the hearing officer's approach:

"The root problem with his analysis is that he failed at the outset to consider how the average consumer would understand the word ORIGIN in the context of the relevant goods. For this purpose, it makes no difference whether one is considering the Respondents' goods (wine in the case of the Word Mark) or the Appellant's goods (Scotch whisky and whisky-based liqueurs). Either way, in my judgment the average consumer would understand the word ORIGIN as referring to the origin of the goods, whether their geographical origin or their trade origin. This would be true in relation to most goods and services, but it is particularly true of both wine and Scotch whisky, where geographical origin is both an important factor in quality and frequently intimately associated with trade origin. It follows that the word ORIGIN is inherently descriptive, or at least non-distinctive, for the goods in issue."

It followed that WM succeeded on its first ground of appeal.

In support of its second, WM argued that the hearing officer's judgment was flawed and contradictory for the following reasons:

"First, he accepted that the vine-leaf device was "eye catching", yet contradicted himself by going on to say it would "go unnoticed". Secondly, he said that "leaf devices upon alcoholic beverages are commonplace" when there was no evidence of that (any more than there was evidence as to consumers' understanding of the meaning of the word JURA). Thirdly, it was not correct to say that the vine-leaf device had no conceptual relevance. It was conceptually relevant both because the use of vine leaves reinforced the message that this was the trade mark of a wine producer and because the globe shape formed by the leaves in the device lent colour to the notion of origin. Fourthly, while it was true that the vine-leaf device could not be verbalised, that did not justify ignoring it when making the visual and conceptual comparisons. Fifthly, his analysis of the impact of the word WINE was flawed because he had failed to give effect to the fact that it was descriptive for wine."

The judge agreed with WM on the first four points but not the fifth. He concluded at para [37] that the hearing officer failed properly to take account of the significance of the absence from the Jura Mark of anything resembling the vine-leaf device.

His lordship rejected the third and fourth grounds of appeal but accepted the fifth that where there is a low degree of similarity between the earlier marks and the mark in suit there is unlikely to be confusion.

Having found for WM on its first, second and fifth grounds, the judge allowed the appeal and ordered the application to proceed to grant.

Should anyone wish to discuss this case or trade mark law in general, he or she should call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or get in touch with me through my contact form,

"The judgment in Bimbo confirms that the principle established in Medion v Thomson is not confined to the situation where the composite trade mark for which registration is sought contains an element which is identical to an earlier trade mark, but extends to the situation where the composite mark contains an element which is similar to the earlier mark. More importantly for present purposes, it also confirms three other points."

He set those out in the following paragraphs:

"[19] The first is that the assessment of likelihood of confusion must be made by considering and comparing the respective marks - visually, aurally and conceptually - as a whole. In Medion v Thomson and subsequent case law, the Court of Justice has recognised that there are situations in which the average consumer, while perceiving a composite mark as a whole, will also perceive that it consists of two (or more) signs one (or more) of which has a distinctive significance which is independent of the significance of the whole, and thus may be confused as a result of the identity or similarity of that sign to the earlier mark.

[20] The second point is that this principle can only apply in circumstances where the average consumer would perceive the relevant part of the composite mark to have distinctive significance independently of the whole. It does not apply where the average consumer would perceive the composite mark as a unit having a different meaning to the meanings of the separate components. That includes the situation where the meaning of one of the components is qualified by another component, as with a surname and a first name (e.g. BECKER and BARBARA BECKER).

[21] The third point is that, even where an element of the composite mark which is identical or similar to the earlier trade mark has an independent distinctive role, it does not automatically follow that there is a likelihood of confusion. It remains necessary for the competent authority to carry out a global assessment taking into account all relevant factors."

Applying that analysis to Mr Salthouse's decision the judge concluded at para [28] that there had been an error of principle in the hearing officer's approach:

"The root problem with his analysis is that he failed at the outset to consider how the average consumer would understand the word ORIGIN in the context of the relevant goods. For this purpose, it makes no difference whether one is considering the Respondents' goods (wine in the case of the Word Mark) or the Appellant's goods (Scotch whisky and whisky-based liqueurs). Either way, in my judgment the average consumer would understand the word ORIGIN as referring to the origin of the goods, whether their geographical origin or their trade origin. This would be true in relation to most goods and services, but it is particularly true of both wine and Scotch whisky, where geographical origin is both an important factor in quality and frequently intimately associated with trade origin. It follows that the word ORIGIN is inherently descriptive, or at least non-distinctive, for the goods in issue."

It followed that WM succeeded on its first ground of appeal.

In support of its second, WM argued that the hearing officer's judgment was flawed and contradictory for the following reasons:

"First, he accepted that the vine-leaf device was "eye catching", yet contradicted himself by going on to say it would "go unnoticed". Secondly, he said that "leaf devices upon alcoholic beverages are commonplace" when there was no evidence of that (any more than there was evidence as to consumers' understanding of the meaning of the word JURA). Thirdly, it was not correct to say that the vine-leaf device had no conceptual relevance. It was conceptually relevant both because the use of vine leaves reinforced the message that this was the trade mark of a wine producer and because the globe shape formed by the leaves in the device lent colour to the notion of origin. Fourthly, while it was true that the vine-leaf device could not be verbalised, that did not justify ignoring it when making the visual and conceptual comparisons. Fifthly, his analysis of the impact of the word WINE was flawed because he had failed to give effect to the fact that it was descriptive for wine."

The judge agreed with WM on the first four points but not the fifth. He concluded at para [37] that the hearing officer failed properly to take account of the significance of the absence from the Jura Mark of anything resembling the vine-leaf device.

His lordship rejected the third and fourth grounds of appeal but accepted the fifth that where there is a low degree of similarity between the earlier marks and the mark in suit there is unlikely to be confusion.

Having found for WM on its first, second and fifth grounds, the judge allowed the appeal and ordered the application to proceed to grant.

Should anyone wish to discuss this case or trade mark law in general, he or she should call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or get in touch with me through my contact form,

.png)

Comments